By Tania Millen, BSc, MJ

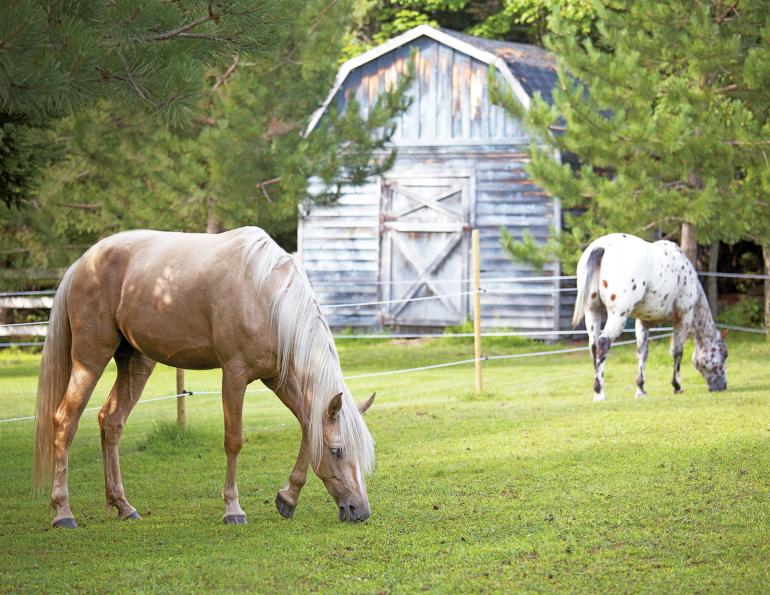

About 1,500 horses run free on the eastern slopes of Alberta’s Rocky Mountains north of Highway 1, which bisects Calgary, and south of Highway 16, which splits Edmonton. Their presence is controversial.

Advocates believe they’re part of the natural ecosystem — just like wildlife — and have historical significance. Indigenous Peoples deeply value the horses and consider them culturally important. A burgeoning number of photographers, artists, and tourists travel to see the horses and record their wonder. Ranchers believe the horses damage range slated for cattle, and occasionally bachelor stallions break their fences. The Government of Alberta considers the horses feral — an invasive species — and has developed a management framework that includes culling or contraception for population control. The science is slim; what’s available is sometimes ignored. Determining the truth is like searching for that proverbial needle in a 500-kilogram round bale of hay.

A beautiful roan mare (above), with her foal, June 2025. Photo: Joanne King Photography

Three foals napping (above) beneath the trees, July 2025. Photo: Joanne King Photography

Stallions (above) fighting to establish dominance over territory and harems of mares for mating. Photo: Joanne King Photography

Questions of Origin

The Government of Alberta (GOA) states that the horses “are descendants of escaped or intentionally released domestic horses, used by First Nations, farmers, ranchers, logging and mining industries, and hunters before and after the Industrial Revolution.”

Related: Complex Rules Protect Canada’s Horses

Dr. Claudia Notzke, Professor Emirata at the University of Lethbridge, says that a precursor to the modern-day horse (the Equidae family) originated in North America about 60 million years ago. They evolved and spread throughout the world, ultimately going extinct in North America during the last ice age which ended roughly 12,000 years ago. Recent data indicates that the Yukon Horse went extinct only about 5,000 years ago — a blink of an eye in the timescale.

“About 500 years ago, things came full circle when Christopher Columbus introduced the Spanish horse to modern-day Mexico in 1519,” says Notzke on The Wildie West podcast. The horses then moved north through Indigenous trade and European colonization. This history matches research by Paul Boyce at the University of Saskatchewan, that determined horses came to the foothills of Alberta’s Rocky Mountains in the 1720s with European colonization.

“But there’s another line of thought,” says Notzke. “There’s increasing evidence… including Indigenous oral history, that small remnant herds of the original North American horse continued to survive [through the last Ice Age].”

If that occurred, then Alberta’s free-roaming horses would be a wildlife species, part of the continental ecosystem. Regardless, explorers’ journals and Indigenous history suggest that horses have been running free on the eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains for about 300 years.

Phoenix’s large band of 22 mares and foals (above). Photo: Joanne King Photography

Vanilla, Anders, and Shekoba in June, 2024 (above). Photo: Joanne King Photography

Under Parks Canada’s definition, the horses would be considered a naturalized species, since they have “lived as part of the natural ecosystem for over 50 years” just like the horses that live in the Sable Island National Park Reserve.

Determining whether they’re feral, a naturalized species, or native wildlife is a cornerstone of management discussions.

What About Genetics?

To further assess the horses’ origins, E. Gus Cothran, a world-renowned geneticist at Texas A&M University, conducted genetic analysis of them. The results indicated a strong predominance of Iberian DNA.

“That’s hugely important,” says Notzke, “because when we look at all the mustang populations in the United States, there are only four groups that exhibit any Iberian lineage. So, these [Albertan] horses have been here a very long time, and they are descended from Spanish colonial horses.”

Related: Equine Rescues, Sanctuaries, and Shelters

Genetic analysis also indicated a strong connection to the Canadian Horse, which came to Canada with French colonists in the 16th Century.

Alberta Government Management

The horses have a colourful history and — like other Canadian species — it includes eradication efforts. The GOA considers the horses feral and manages them under Alberta’s Stray Animal’s Act and Horse Capture Regulation.

From the 1920s to 2015, the horses had bounties on their heads or were rounded up as pests with the provincial government’s blessing. According to the Alberta Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Resource Development, there were 212 horse capture licences issued for the November 2011 to February 2012 capture season. The trapped horses were often sold for meat.

Since 2008, the GOA has been counting horse numbers across six Equine Management Zones (EMZs). Horse population minimums have ranged from 354 in 2008 to 1,712 in 2018 to 1,478 today, with the highest populations of horses located in the area west of Sundre.

However, Notzke says there were tens of thousands of wild horses in Alberta during the colonial explorer era. If that’s the case, then the horse population has been reduced to a fraction of what it was.

According to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) SSC Equid Specialist Group, a minimum of 2,500 mature individuals of one species constitutes a threshold below which the species may be considered endangered. The free-roaming horse population in Alberta is much lower than the IUCN threshold and the animals are spread over 5.5 million acres of public land in isolated herds that don’t interact. So, if the horses are proven to be unique, they will also likely be considered endangered.

Above: Joanne King Photography

Above: Joanne King Photography

Above photo courtesy of HAWS

In 2013, GOA formed an advisory committee due to public pressure. The main purpose of the Feral Horse Advisory Committee today is to provide advice and recommendations to GOA. However, Committee consensus is not required and the government can choose whether to follow their recommendations. Members include representatives from horse advocate groups; non-profit organizations supporting wilderness, fish, and wildlife; an outfitters group; a ranch; rangeland support; First Nations; a forestry operation; universities; and the RCMP. The last publicly available minutes of the Committee are from 2021, and members cannot speak about discussions outside Committee meetings.

In 2023, GOA published the Feral Horse Management Framework, which emphasizes the need to balance impacts on the eastern slopes rangeland, taking into account the competing interests of recreation, forestry and resource extraction, wildlife, livestock, and horses. It also provides horse population thresholds for each EMZ. GOA plans to maintain population limits by capturing and removing horses, or through the use of contraception.

Framework Concerns

Wayne McCrory, a long-practicing registered professional biologist who wrote The Wild Horses of the Chilcotin: Their History and Future, declared the Framework scientifically deficient.

He wrote that “cattle outnumber wild horses by seven times during the active rangeland growing season and are responsible for historic overgrazing, yet their past and present impacts on rangeland health are insufficiently addressed in the Framework.” He notes that other impacts including invasive plants, industrial forestry, oil and gas development, roads, trails, and extensive off-highway vehicle use aren’t considered either.

McCrory further noted that the Framework “fails to take into account the role that natural ecosystem factors play in balancing horse numbers, such as predation (wolves, mountain lions, grizzly and black bears), extreme winters, droughts, and movement from one EMZ to another.”

Photo (above): Joanne King Photography

Photo (above): Joanne King Photography

Photo (above): Joanne King Photography

Finally, McCrory wrote that “intervention population control measures appear unwarranted and will do little, if anything, to protect and restore rangeland health without addressing all the cumulative impacts.”

While GOA continues to assert that wild horses are pests whose numbers must be reduced, McCrory’s comments suggest that competing interests are at the heart of Alberta’s wild horse discussion.

Competing Interests

“There’s been an ongoing narrative that horses are a problem,” says Brain de Kock, P.Ag., consultant for Zoocheck Inc.

Related: Heroic Bystander Rescues Wild Foal Stranded on Cliff’s Edge

Cattle ranchers pay to lease land from GOA to feed 8,544 cattle. If that grass is chewed up by wild horses, it affects the number of cattle that can range the land and in turn, negatively affects the ranchers’ livelihoods. However, during his research with 120 trail cameras and five GPS-tracking devices, Boyce found that “counter to expectations, horses avoided native rangeland in summer, compared to greater selection of forestry cutblocks.” In other words, the horses preferred disturbed areas such as forestry cutblocks over the grassy meadows that cattle grazed.

According to de Kock, the Help Alberta Wildies Society (HAWS) has repeatedly requested access to annual provincial rangeland health reports to ascertain how much grass is available, how many cattle the range can support, and whether the horses are damaging the land.

Lincoln’s band of mares (above) in January, 2025 with four 2024 foals. Photo: Joanne King Photography

Anders, Adria, Shikoba, with Gambler behind (above). Photo: Joanne King Photography

Photo (above): Joanne King Photography

In 2024, the 2015 annual provincial rangeland health reports were released to Zoocheck Inc. and de Kock subsequently reviewed over 4,000 pages of data, charts, photographs, and summaries.

“Horses are not negatively impacting the landscape,” says de Kock. “Ninety-five percent of the impacts outlined in the 2015 rangeland health reports were due to industrial human extraction activities, logging, pipelines and cutlines, new roads being built, off-highway vehicles, invasive species taking hold, and about seven times as many cattle as horses on the landscape. Horses are not the primary driver of the negative impacts [on the land] — it’s industry.”

Although HAWS and Zoocheck Inc. continue to request access to annual provincial rangeland health reports, nothing further has been released for review.

Population Increase or Decline?

“Twenty years ago, the narrative was that the horses were doubling in population,” says de Kock. “That wasn’t true then and it’s not true now. It’s physically impossible.”

Aerial surveys by GOA and those conducted independently by HAWS don’t support this assumption. Boyle found that Alberta’s free-roaming horse population has been declining since 2018.

Boyce states that foals typically make up eight to 15 percent of the feral horse population. He writes, “The proportion of foals… declined each year throughout the study, matching recent declines in foal survival detected by local observers, and declines in the population observed through aerial minimum counts.”

HAWS has also collected anecdotal evidence through their 60-plus cameras installed on forestry lands that only about 10 percent of the horses’ foals survive the first year. Mortality from large predators such as bears, cougars, and wolves is common, and HAWS has recorded the hair-raising sounds of a grizzly bear catching and killing a foal.

Silver Dawn (above), a beautiful mare from Trenton’s band. Photo: Joanne King Photography

Photo (above): Joanne King PhotographyHAWS estimates that only about 10 percent of foals survive the first year. Photo: Joanne King Photography

The horses’ lives are truly integrated with the ecosystems where they eke out a living.

“Unlike domesticated horses, Alberta’s wild horses live in self-sustaining herds, follow natural migration patterns, form strong social bonds, and adapt to the landscape just like other wildlife,” writes Sam Pedersen, a member of the Sturgeon Lake Cree First Nation in a February 10, 2025 letter to the Honourable Rick Wilson, then-Alberta Minister of Indigenous Relations. “They survive harsh winters, find food in rugged terrain, and evade predators — indicating their high adaptation to the landscape.”

Part of Indigenous Culture

“Horses are not just animals but are woven into Indigenous cultural and spiritual life,” says Pedersen on The Wildie West podcast. “The reserves which Indigenous Peoples live on are Crown land, as is the land that the horses occupy, so Indigenous Peoples should be consulted. Treaty 8 was signed in 1899 and it mentions the Crown’s obligations to Indigenous Nations, stating that each Chief shall receive one horse, harness, and wagon for the use of his Band. So, horses were key to the survival of the community.

“I feel the horses don’t have a voice and they are being negatively impacted by the government,” Pedersen explains. “The assimilation of these horses very much mirrors how Indigenous Peoples were treated [historically during colonialism].”

Culling and Contraception

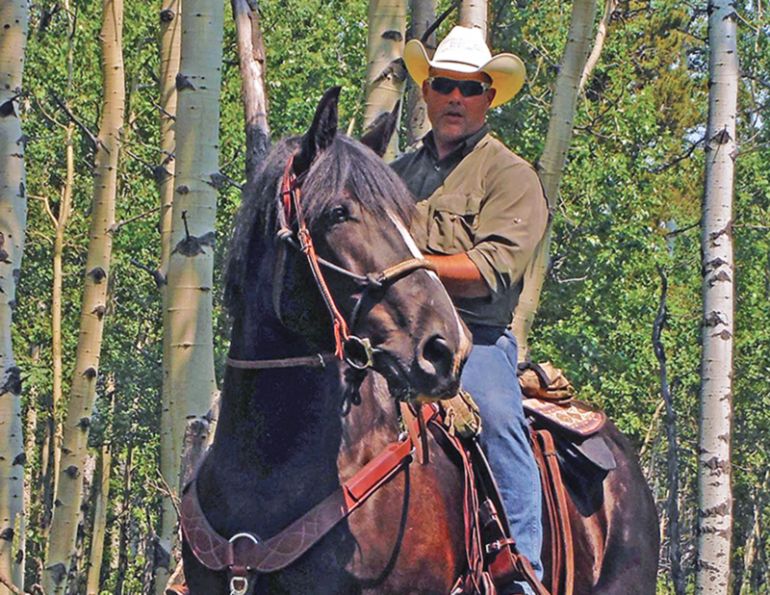

The Feral Horse Management Framework allows capture permits to be issued to specific groups to capture distressed or nuisance horses and arrange their adoption by suitable owners. Wild Horses of Alberta Society (WHOAS) is one of those groups.

Jack Nichol, President of WHOAS, explains that the horses often become a nuisance in the winter.

“They’re looking for feed, and the stallions may be under pressure from other stallions,” says Nichol. “Sometimes gates are left open by quadders [all-terrain vehicle riders] so they get onto the road, or a fence may be down and they end up on somebody’s property.”

Once the horses are off public forestry lands, WHOAS’ permit says that they cannot haze the horses back onto those lands, and the horses must be captured.

“We work with brand inspectors before picking up the horses and bringing them to our facility,” explains Nichol. “We work with the horses and then adopt them out. At this point, we’ve relocated over 200 head of horses.”

WHOAS has relocated more than 200 horses that were considered a nuisance or distressed. WHOAS works with them and arranges their adoption by suitable owners. Photo: Ramona Kirchner

Nichol says the government is trying to come up with a management strategy that will hopefully satisfy all of those involved in Alberta’s free-roaming horse community.

“We’re the only ones helping them remove horses and our facility can only handle about 30 horses at one time,” says Nichol. WHOAS would prefer to see about ten horses removed from the herds annually, rather than larger culls which challenge them to find enough adoption homes for the horses.

“We’re hoping to remove some of the bachelor studs from an area where there’s a higher population,” says Nichol. At the same time, WHOAS would like to capture mares in a trap so they can administer a contraceptive to help the government control horse numbers.

“We want to conduct this three-year [contraceptive] program to see what it does to the population numbers,” says Nichol, explaining that the vaccine has been used frequently in the United States. “With the contraceptive, the mares are bred but they don’t become pregnant for approximately three years.”

According to Nichol, GOA planned to begin the contraceptive program in 2025 but it’s on hold until 2026.

Debbie McGauran, a HAWS representative, disagrees with the approach.

“The problem with the program is that the drugs they’re proposing to use are for research purposes; they’re not supposed to be for herd management,” McGauran says. “What they want to use it for is not approved by Health Canada.”

She explains that the drug is supposed to work for two or three years but information HAWS is receiving from the USA indicates that some mares are permanently sterilized and some can’t have foals for seven or eight years.

“You’d be decimating the population,” McGauran says. “It’s equine genocide.”

Photo (above): Joanne King Photography

Photo (above): Joanne King Photography

Lacy, Dearg and Arturo, with a deer in the background, June 2024. Photo (above): Joanne King Photography

Social Licence

In 2024, R.A Malatest & Associates Ltd. conducted a public survey of Albertans to poll their knowledge and opinions on free-roaming horse management in the province.

Of the 729 respondents, 82 to 95 percent were aware of the horses, their history, and social behaviours. Almost three-quarters felt that the horses were important for Alberta’s culture, history, and tourism. Two-thirds of respondents supported a hands-off management approach. Over 85 percent provided comments supporting wild horse populations in Alberta.

Related: CPCHE: Guidelines for the Humane Treatment of All Horses

The report stated, “The overwhelming majority of participants expressed preference for a hands-off management approach and additional protections to ensure the sustainability of the wild horse population. These findings suggest strong public support for policies and initiatives that prioritize the preservation of Alberta’s wild horses and their habitat.”

What’s Next?

“Why is the government so obsessed with removing the horses?” de Kock asks rhetorically. “The [government] seems hell bent that something needs to be done — but for whose benefit? Why are the horses being scapegoated?”

Boyce writes that “increasing socio-political conflict regarding feral horse management, their role, and their impacts in the Foothills ecosystem highlights a growing need for nuanced management approaches predicated on robust ecological information.”

“Indigenous people need to be consulted about the wild horses being moved, captured, and sterilized,” says Pedersen. “The stories and perspectives of Indigenous Peoples matter.”

Rather than continuing to manage the horses, HAWS would like to see them reclassified as a naturalized species and left alone.

HAWS would like to see the horses reclassified as a naturalized species and left alone. Photo (above) courtesy of HAWS

“Even though the government has said that the horses should have a place on the landscape, they’re not willing to put their money where their mouth is and change [the horses’] designation to a naturalized species to ensure that the horses stay on the landscape,” says McGauran.

Given the evidence that Alberta’s free-roaming horses do not negatively affect cattle range, may be a unique and historically significant species that could substantially support reconciliation efforts, and have strong public support for protection, GOA’s rationale remains unclear.

In June 2025, GOA advertised for a Terrestrial Invasive Species and Feral Horse Management Coordinator job. In a July 2025 media scrum, Premier Danielle Smith supported the sterilization of wild horses. This suggests that GOA may be doubling down on wild horse population suppression regardless of public opinion polls and scientific data. And that means the fate of Alberta’s free-roaming horses continues to be uncertain.

For more information:

- Alberta Mountain Horse

- Government of Alberta Feral Horse Management Framework

- Help Alberta Wildies Society (HAWS)

- IUCN SSC Equid Specialist Group

- The Wildie West podcast

- Wild Horses of Alberta Society (WHOAS)

- Zoocheck Inc.

Related: Readers Weigh In on Alberta's Free-Roaming Horses - View Website Poll Results and Comments

Related: Canada’s Wild Horses - An Uncertain Future

Related: Good Deeds: Feeding Wild Horses

Main Photo: Joanne King Photography